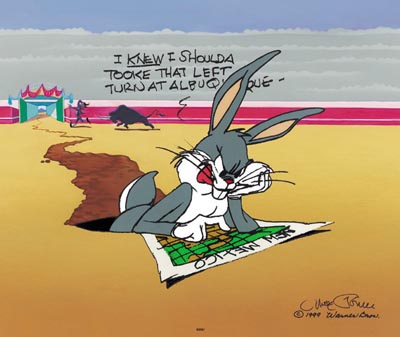

Wrong Turn at Albuquerque?

Privacy has become less valued by society than in previous eras. Whether it’s security, convenience or the seemingly inevitable march of technology, we talk of “managing” privacy; of the balancing of business needs with individual interests; of data being the new currency; of generational change in attitudes; all ultimately leading one down the road of “privacy is dead” and of a need to “get over it”. You look at this type of roadmap and you can’t help but wonder if we’ve pulled – à la Bugs Bunny – a “wrong turn at Albuquerque”.

Two extraordinary stories suggest its time to re-examine privacy as a societal value. The first is the story of Veterans Affairs Canada (“VAC”), headquartered in Prince Edward Island (“PEI”), and Sean Bruyea. For those not in Canada, press coverage detailing the story can be found here, here and here. In my view, Mr. Bruyea himself cuts to the chase with this quote:

“There is a culture in that department that thinks that they have the monopoly on deciding what veterans – disabled or not – and their families deserve, and they believe they do not have to take any recommendations, consultation whatsoever from the veterans,” Mr. Bruyea said in an interview.

This arrogance, this paternalism – that they don’t have to listen to veterans in my case – has extended to the point where they believe they can manipulate medical files without the permission of the veterans and send it anywhere within the department to whomever in the department.”

A cultural issue? Not surprising in a province (PEI) whose population is smaller than an Ottawa suburb and where everyone knows pretty well everything about one’s neighbours. Why wouldn’t that attitude towards personal information be carried over to the workplace? We warn people about outsourcing to India or China and the different cultural norms to be found there. Why would a small, mostly rural province like PEI be any different?

A cultural issue? Not surprising in a province (PEI) whose population is smaller than an Ottawa suburb and where everyone knows pretty well everything about one’s neighbours. Why wouldn’t that attitude towards personal information be carried over to the workplace? We warn people about outsourcing to India or China and the different cultural norms to be found there. Why would a small, mostly rural province like PEI be any different?

The second story involves Rutgers and the tragic death of Tyler Clementi. National Public Radio’s blog “The Two Way” casts the affair in cultural terms as well and states the facts plainly:

Clementi’s roommate Dharun Ravi reportedly activated the webcam on his laptop and broadcast Clementi and another man having sex, and he shared it with the world, live. He allegedly tweeted about it, chatted about it, and invited others to watch when he thought Clementi would be having sex again. Clementi found out, and a few days later he threw himself off of the George Washington Bridge.”

After noting several other cases, NPR’s blog post blandly concludes that people don’t yet seem to have to have caught up with technology.

Most people were “shocked” at these two stories – believing the invasion of privacy to be too egregious…too “wrong”…to pass unremarked. There are legal remedies being pursued by the relevant parties but the fact of the matter is that we seem to be concerned only with the scandalous, sensational stories as opposed to the every day occurances of privacy violations. How many millions of personal records have been lost in data breaches over the last five years? Yet we almost have become blasé about it – as long as it’s someone else’s personal information. (Joe South’s song “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” springs to mind.)

Yes, we have personal information protection laws. Yes, we have data protection authorities and Privacy Commissioners to enforce them. One might even acknowledge calls to avoid “zero-sum” scenarios and build privacy into the design of initiatives and technology. But, at the end of the day, privacy is a cultural issue about respect. And if you want it, you have to give it.

So before we think about who should get fired, fined, sued, expelled or imprisoned because of the consequences arising from a

So before we think about who should get fired, fined, sued, expelled or imprisoned because of the consequences arising from a  breach of someone’s privacy, it might be better to think not in terms of laws, enforcement or remedies but rather in terms of how we want to be treated as individual human beings. We need to think in terms of how we want other people to handle our information as they go about their everyday business; of how we would want to act if we were handling our own information. In putting ourselves in those shoes, we gain a new perspective – one where words like trust, respect and human dignity have not been so cheapened by those who simply want to mine our data for politics or profit.

breach of someone’s privacy, it might be better to think not in terms of laws, enforcement or remedies but rather in terms of how we want to be treated as individual human beings. We need to think in terms of how we want other people to handle our information as they go about their everyday business; of how we would want to act if we were handling our own information. In putting ourselves in those shoes, we gain a new perspective – one where words like trust, respect and human dignity have not been so cheapened by those who simply want to mine our data for politics or profit.

Interesting that the “Golden Rule” which dates as far back as Jesus of Nazareth is still not a fundamental in our culture. “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.”

I concur that privacy needs to be measured and treated more on its impact to individuals than as a policy concept that few seem to understand or appreciate.