The Continuing Travails of Digital Identities

I was asked the other day if I thought identity issues were any different from when I dealt with them at TBS some 10 years ago. I paused, thought about it, hummed a bit, thinking of the intervening work done — Oasis (SAML), Liberty Alliance, WS-* — and finally said I didn’t think so. The central concerns and issues — the provisioning of digital identities for use by multiple organizations in the same “identity ecosystem” — remain. For entities wanting to interact with an individual outside of that organization (e.g. in e-commerce, e-government, eHealth, shared services contexts) there is still the question of who they are and what can they do? The answer remains the same as it did in the 90s – it depends.

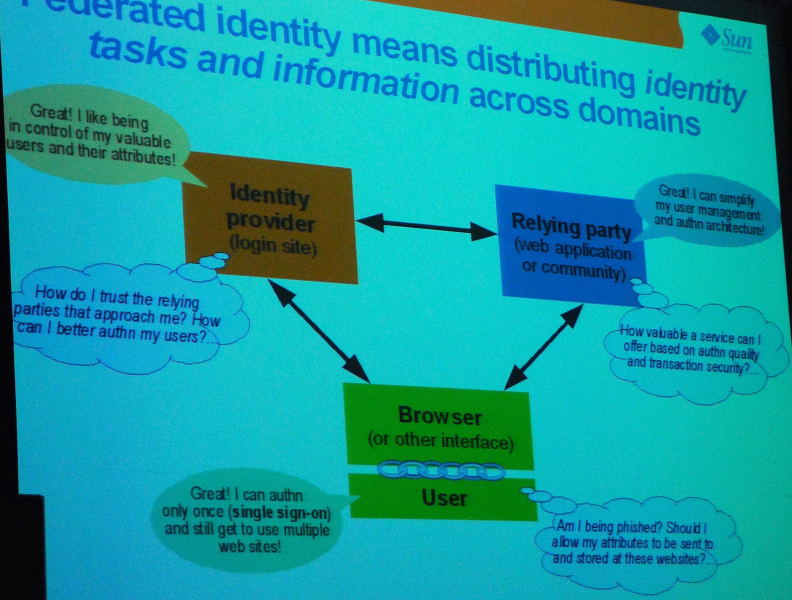

The identity model most talked about these days is federated identity management (“FIM”). There are several technical definitions of FIM but the core concept is the reliance by one domain on the identification of an individual by another domain. Theoretically, the issue shifts from the identification of the individual who presents a credential to the verification of the credential itself.

The eventual value of a “federation” is to eliminate redundant user administration and reduce provisioning and support costs. As we move further down the line to the “Internet of Things” (e.g. Smart Grids) the need for trusted digital identities will necessarily extend beyond people to devices. However, at the end of the day, the cornerstone for FIM is trust: trust by Domain Owner No. 1 that Domain Owner No. 2 has properly “identified” the user accessing the information on Domain No. 1’s system (whether or not those identities have been shared with a central identity store).

Identification is closely linked to authentication (we’ve proven who you said you were) and authorization (what you’re allowed to do). FIM is essentially the identification aspects of PKI systems talked about in the 1990s (which explains the reference to 10 years ago and Treasury Board) where “Local Registration Agents” were to vet the identity of the person to be subsequently associated with a digital certificate.

Identification is closely linked to authentication (we’ve proven who you said you were) and authorization (what you’re allowed to do). FIM is essentially the identification aspects of PKI systems talked about in the 1990s (which explains the reference to 10 years ago and Treasury Board) where “Local Registration Agents” were to vet the identity of the person to be subsequently associated with a digital certificate.

The reader’s digest version of why I said “I didn’t think so”? Nothing’s really changed. Proponents of FIM (or any identity system) say you can put in place the trust frameworks to make it work; naysayers tend to emphasize the risk of things going wrong. FIM is certainly do-able but higher risk services like eHealth and eGovernment haven’t yet made the commitment to trust other parties. You will see FIM accepted in business (risk being less than the benefits) and might see a central identity store for eGovernment services (think of the Canadian government’s former “ePass”) but FIM in eHealth hasn’t materialized yet.

The concept necessitates a shift from “vertical” to “horizontal” thinking in terms of identity management but interestingly it also represents a shift in technological risk to legal risk.

What are the legal risks? They fall into basically four categories: Identification, Privacy, Authentication and Authorization.

- Identification risk concerns how much do we trust the identification process and how vigorously is it followed.

- Privacy risk concerns the rules surrounding the use and disclosure of the personal information collected. I think this tends to be more an issue in the United States than Canada or Europe given the lack of comprehensive and uniform privacy law there but it depends on how it is done (i.e. no systemic, searchable or centralized collection of transaction information)

- Authentication risk pertains to just who is the person behind the name. It may be Stephen Harper but is it the Stephen Harper who is Prime Minister or someone else. The attributes linked to the online identity determine what that person may see.

- Authorization risk concerns what an online identity can do. Health poses unique problems in this space since a complete stranger may need to access a file for a reason that isn’t readily known at the time of access.

The last two risks are more of a concern for relying parties (concerned about getting it right) and those who verify identity (who may be liable if they get it wrong).

All of these risks have the potential to create liability for each of the players (subject, relying party, identity provider). For example, what if the subject provides incorrect identity information or fails to protect the password or token necessary for asserting an online identity? What if the identity provider fails to follow it’s own processes? What if a Relying Party relies on an identity but there are clues that it shouldn’t? You get the idea – things can go wrong and when they do who gets the blame.

I’m not suggesting things will go wrong but FIM involves rules or agreements between the players in the ecosystem and this will be a heavily debated topic in crafting those rules or agreements (unless there is a centralized as opposed to a collaborative or consortium model used).

Further complicating matters are fundamental questions as to who is going to own or host that digital identity. It is arguable that governments alone cannot or should not determine what constitutes a digital identity.

Despite impressive efforts over the last decade, online identity remains a “hot topic”. At the end of the day, though, identity isn’t just about technology or law but also trust.

While I wholeheartedly agree with your assessment that not much has changed in the last decade (or more), I don’t share your optimism that we see a solution on the horizon. The notion of a wholly adopted agreement that allocates those risks (the goal of those seeking consensus) or the notion of an acceptable edict from lawmakers who will pick winners and losers in the risk allocation (much as the lords of software attempted to impose their will through UCITA in the States) is still a dream at best. And, it is the lack of a way to allocate those risks that suggests to me that much of what we dream for electronic-only transacting will likely never move beyond what I can order from Amazon.