Canada & The PATRIOT Act: Get Over It

It is somewhat fitting that Halloween and the anniversary of the enactment of the PATRIOT Act are close together. In Canada, the latter, which turned 10 last week, has come to embody fear about government access to personal information. The troubling part is that this fear may needlessly complicate life for everyone in this country.

For those not familiar with the PATRIOT Act, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (“FISA”) provides American authorities with the power to gather intelligence on foreign agents in the United States and abroad, pursuant to orders issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

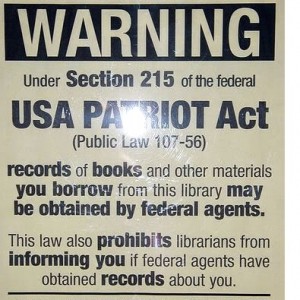

To better protect the United States against international terrorism and against foreign intelligence activities, the PATRIOT Act amended FISA to allow US authorities to obtain records and other “tangible things” (Section 215) and that intelligence gathering need only be “a significant purpose”, rather than the sole purpose, of FISA searches or surveillance in the US (section 218).

Section 505 of the Patriot Act lowered the threshold for the issuance of “national security letters” which require financial institutions, telephone companies and ISPs to disclose information about their customers. The threshold went from requiring specific facts to simply being relevant to an authorized investigation. The scope of coverage was later expanded to include travel agencies, real estate agents, the US Postal Service, jewellery stores, casinos and car dealerships.

Section 505 of the Patriot Act lowered the threshold for the issuance of “national security letters” which require financial institutions, telephone companies and ISPs to disclose information about their customers. The threshold went from requiring specific facts to simply being relevant to an authorized investigation. The scope of coverage was later expanded to include travel agencies, real estate agents, the US Postal Service, jewellery stores, casinos and car dealerships.

In Canada, the popular view appears to be that American authorities use these powers to obtain access to personal information located in Canada about Canadians because of such information is in the custody or control of an American company.

It doesn’t help that US courts have no difficulty ordering disclosure of records held outside the US, as long as a person or organization — subject to the US court’s jurisdiction — has a legal or practical ability to access those records. Some American courts have found that control of records exists whenever there is a US parent-Canadian subsidiary corporate relationship.

While failure to comply with a FISA order may result in contempt charges, section 215 relieves a person of liability in the US for complying with a FISA order. As a result, American corporations have an incentive to comply with such orders — even if it may breach contractual or legal obligations in other countries, including Canada.

By the way, if you thought the PATRIOT Act was all about fighting terrorism, read this story and think again.

Is this “easier” access to your “state-side” records the real issue though? If people in Canada are concerned about law enforcement access through the PATRIOT Act, why aren’t they saying anything about similar Canadian laws?

What laws? See Part II of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act which allows designated judges from the Federal Court secret to issue warrants authorizing (1) the interception of communication, (2) obtaining any information, record, document or thing by (a) entering any place, (2) searching, removing and examining any thing, or (installing, maintaining or removing any thing.

Then read s. 273.65 of the National Defence Act with respect to the abilities of the Communications Securities Establishment to intercept communications pursuant to a Ministerial authorization.

Even in PIPEDA, some access requests need to be run by law enforcement authorities and denied if an institution is:

“of the opinion that compliance with the request could reasonably be expected to be injurious to (a) national security, the defence of Canada or the conduct of international affairs; (a.1) the detection, prevention or deterrence of money laundering or the financing of terrorist activities; or (b) the enforcement of any law of Canada, a province or a foreign jurisdiction, an investigation relating to the enforcement of any such law or the gathering of intelligence for the purpose of enforcing any such law.”

Just as our federal Privacy Commissioner cooperates with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (see Accusearch Inc.) law enforcement authorities in our two countries cooperate as well. The process of getting information under mutual legal assistance treaties can be slow but the mechanisms do exist and, in an emergency, you can imagine things move very quickly on an informal basis. https://cryptocasinohk.com/

You may (or may not) question the interpretation, effectiveness or ongoing utility of these intelligence gathering tools but the legal frameworks to allow their use exist both in Canada and the United States. Why then do people single out the PATRIOT Act? Perhaps not unsurprisingly, people cite the PATRIOT Act and “privacy concerns” when they really have another agenda.

It seems that people are starting to recognize this grandstanding for what it is. We’re seeing a more critical eye being cast on PATRIOT Act arguments. See this 2009 Lakehead University arbitral decision and, reported in this blog post, this 2010 Alberta arbitral decision.

In the emerging world of cloud computing, Canadians will have to recognize that more of our personal information will go “offshore”. If it does, should law enforcement access be the primary concern? I think we need to worry less about “where” and more about “how secure” and “how accessible”.

Section 273.65 of the NDA only refers to the intercept of foreign communications, not the communications of Canadians. CSE, or DND, are not allowed to intercept on Canadian Citizens. Also, while you discuss the legal means to gather the data, you seemingly do not weigh in on the intelligence gathering use of the Patiot Act. I am still adamant that my data does not go accross the border if I can do anything about it. With regard to the cloud; simply a new name for the Data Centre!

The provisions of the US Patriot Act have allowed for surveillance to take place on an industrial scale. This has shifted surveillance from an activity directed against individuals to an activity directed against society at large: all credit card transactions, bank deposits and withdrawals, and other financial transactions; all emails; all web accesses including all searches; all car rentals, hotel bookings, and other travel arrangements; in other words, just about everything. On just about everyone in the US. It is a scale and breadth of surveillance unsurpassed by any previous efforts. Even the East German Stasi didn’t have access to such comprehensive information on its citizenry. “Warrantless wiretapping” of the Internet has become a fact of life for Americans and all of it has been aided immeasurably by the Patriot Act. The Act has helped the NSA to effectively turn online America into a foreign country for legal purposes.

For a good non-technical description of the scale and extent of surveillance, see the Washington Post-led Top Secret America at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/topsecretamerica/ Since 9/11, more than 1,200 government agencies and 2,000 private corporations at over 10,000 locations within the United States have contributed to a vast network supporting this activity.

Thanks to the the persistence of campaigners such as EFF, some details of NSA’s surveillance network have been made public, starting in 2006. For example, the link below analyses the wiring plans and fibre schematics provided by a former AT&T technician and showed how optical fibres running through AT&T’s San Francisco hub had been spliced and tapped to take much of the United States’ west coast Internet traffic into analysis centres. See http://www.eff.org/files/filenode/att/presskit/ATT_onepager.pdf for a good overview. Such schemes became operational post 2001.

The volume of data is staggering. According to declassified documents made available by the US Comptroller’s office for the Department of Defense, the US government’s fiscal 2012 budget includes $860.6m to build a high performance computing center at the NSA’s Fort Meade, Maryland, headquarters facility. That’s just the cost of the facility alone, not the cost of the servers, storage, and networking gear that will inhabit the data center. See http://comptroller.defense.gov/defbudget/fy2012/budget_justification/pdfs/07_Military_Construction/12-National_Intelligence_Agency.pdf This is in addition to the NSA’s $1.53bn 65 megawatt data center on a 240-acre site at the Camp Williams National Guard facility in Utah. Construction began on this data center in late 2009 and is expected to be completed in May 2014.

Where does this leave Canadians? Among other concerns, Canadian health records and provincial and territorial government databases should not be hosted outside of Canada or on servers within Canada whose databases are accessible from outside Canada. Much more scrutiny should be given to Canadians’ financial data and its privacy and security. And yes, there needs to be a full review of the practical effects of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act. Canadian universities should be involved in such activities.

By the way, there is nothing in cloud computing that prevents full control of data. Encryption, physical security and territorial hosting requirements can be effectively applied to secure such data, if the will is there to do so. As the previous commenter noted, the Cloud is just another name for a data centre. But the Cloud promises to become a very large, very distributed, and very poorly secured data centre. Such developments provide even more reason for flinty-eyed scrutiny. Now is exactly the time for Canadians to be more–not less–concerned about the US Patriot Act and its reach.

The perception of most businesses in Canada is that once personal information crosses our borders into the US, it immediately becomes high risk. Most people are unaware that if US or Canadian authorities really want personal information — they’ll get their hands on it. I’ve written on this briefly in a similar post over a year ago: http://www.privacysense.net/canadian-equivalent-patriot-act/

You’ve gone a bit more in depth and introduced other angles. Great post.

Cheers,

Mark