Revenge Porn & Canadian Law

Whenever a new technology arrives, society always plays “catch up” to determine what norms to apply to the use of that technology. It’s probably how we got traffic lights after the advent of automobiles. One “by-product” of smartphone cameras and the Internet is “revenge porn”. The Internet didn’t invent the problem but it sure magnifies it with devastating effect.

“Revenge porn” is the public upload of sexually explicit material without the consent of all participants. Sometimes the upload is accompanied by personal information identifying one of the individuals. The creation of this content is often consensual during a relationship but its “use” can change after the end of the relationship. Revenge porn is a lot more common than one might think. In 2013 MacAfee conducted a study, which revealed that 1 in 10 ex-partners threatened to post risqué photos of their ex and that 60% of those individuals had carried through on the threat.

The latest illustration of the problem is a January 2015 decision out of West Australia, Wilson v. Ferguson, in which the defendant posted photographs and videos of the plaintiff on Facebook. The distress and embarrassment for Wilson was immediate and she took an extended leave of absence without pay. Interestingly, as a result of the incident, the company terminated Ferguson’s employment some 10 days after the posting on Facebook. This last fact may be a more telling warning to anyone thinking of using revenge porn to get back at an ex.

Wilson sued and the Supreme Court of West Australia awarded an injunction and damages of close to $50,000 for a breach of confidence. Australian commentators here and here discuss Wilson in more detail and its potential impact on privacy law in that country. The case also presents a useful reminder of a 1967 English case, Duchess of Argyll v Duke of Argyll, [1967] CH 302 (which does not appear to be readily available on line):

“…the intimate nature of a personal relationship between two people may give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence such that, without express statement to that effect, private and personal information passing between those people may in certain circumstances be imbued with an equitable obligation of confidence.”

In Ontario, a claim of intrusion upon seclusion, recognized in Jones v Tsige, can be readily used in a revenge porn situation. The criteria for damages would be met since the nature of the act; the relationship between the parties; the existence of distress or embarrassment; and the conduct of a party are all criteria to be considered by the court in any damage award.

In Ontario, a claim of intrusion upon seclusion, recognized in Jones v Tsige, can be readily used in a revenge porn situation. The criteria for damages would be met since the nature of the act; the relationship between the parties; the existence of distress or embarrassment; and the conduct of a party are all criteria to be considered by the court in any damage award.

In those provinces that have not yet recognized this tort, I suspect the very nature of a claim involving revenge porn would serve as a catalyst for the adoption of an intrusion upon seclusion tort. In provinces with a statute-based privacy tort (BC, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland), I think revenge porn would be egregious enough to meet the requirements of those statutes.

It would also be interesting to see what would happen if a claim of workplace harassment was made against an employer because of the revenge porn activities of an employee (this may explain, in part, Mr. Ferguson’s swift termination of employment). Also, given the decision in Ross v. New Brunswick School District No. 15, employers should be mindful that they may have to take action in revenge porn cases even if it involved off-duty conduct by employees against non-employees. I haven’t come across any cases using this approach but, in the right fact situation, I’m not sure it would be unreasonable to make such an argument.

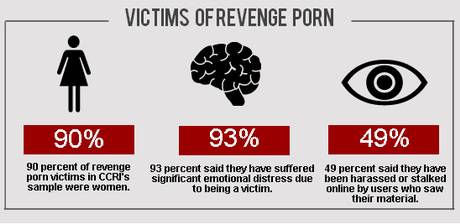

Finally, in a criminal law context, Bill C-13 received Royal Assent on 9 December 2014. Among other things, Bill C-13 adds a new s. 162.1 to the Criminal Code, which makes it a offence to share sexual images with a third party without the subject’s consent. Those found guilty can face up to five years in prison. The Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (“CCRI”) indicates a number of American states have criminalized revenge porn and the UK is on the verge of doing so.

Not everyone agrees this is the correct approach: with respect to Bill C-31, the Canadian Criminal Justice Association argued that the problem should be addressed outside the criminal justice system. An American argument against criminalization is presented here. Depending upon context, we may yet find ourselves fine-tuning the criminal law in this area.

To the extent commercial entities in Canada may not want to “take down” such materials (e.g. porn sites), publishing or hosting such materials could see such companies face claims of copyright (no license to publish) and data protection (no consent to disclose) violations.

While Canada appears to have sufficient legal tools in place to address the problem of revenge porn, the real issue is how best to get the message across that the “publication” of such content is not simply a “private affair” between individuals. Not all victims will be like Ms. Wilson in West Australia and go to court. It’s not just a violation of privacy anymore but increasingly a violation of a societal norm.

steel building builder

Profit from amazing read more currently open for service in addition on sale now!