Privacy & Law Enforcement

Under PIPEDA, “lawful authority” arises as a preliminary matter when an organization is approached for a request for personal information by a “government institution or part thereof”. While a “clarification” of “lawful authority” is one of the proposed amendments to PIPEDA, the issue is really about whether organizations should disclose to law enforcement authorities. While consent to disclose personal information may not be necessary, disclosure by the organization is still voluntary. When and how should organizations cooperate with law enforcement authorities?

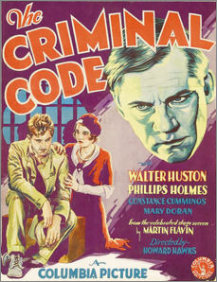

People often assume “law enforcement authority” means police. In Ontario, the Police Services Act (“PSA”) sets out the duties of police officer. When part of your job is to investigate crimes and enforce the law, especially the Criminal Code, you pretty well have lawful authority to “ask”. This is a gross oversimplification of “lawful authority” but it tends to work for most situations where the request comes from police. Where the question really comes up (i.e. “do they have lawful authority?”) is where other types of government personnel conduct investigations (e.g. inspectors or auditors).

People often assume “law enforcement authority” means police. In Ontario, the Police Services Act (“PSA”) sets out the duties of police officer. When part of your job is to investigate crimes and enforce the law, especially the Criminal Code, you pretty well have lawful authority to “ask”. This is a gross oversimplification of “lawful authority” but it tends to work for most situations where the request comes from police. Where the question really comes up (i.e. “do they have lawful authority?”) is where other types of government personnel conduct investigations (e.g. inspectors or auditors).

Assuming lawful authority is established and absent a warrant or order, the decision remains voluntary: the organization still has to decide whether to provide the personal information in question. So how does it do that? What criteria does it use in deciding to cooperate with law enforcement? If approached, is there an internal process to follow?

While the following is far from a comprehensive list, if you don’t have a “law enforcement cooperation” policy, here are some things to ponder in creating one:

Who makes the decision to cooperate? If you don’t have a General Counsel, is that person obliged to check with external legal counsel?

Is the nature of the personal information particularly sensitive?

Could the individual concerned have a reasonable expectation of privacy about that information?

Under what circumstances will the organization cooperate with law enforcement authorities?

-

- Only when there is a danger to organization’s property or personnel? You can try it out here to know about the history behind the property.

- Only in exigent circumstances (e.g. a missing person or a person identified as a danger to themselves)?

- In all circumstances, unless there is a risk to the organization’s property or personnel or unless the cooperation is disruptive to business operations?

Should the organization consider the perspective of its clients? (A large car rental company may answer the question differently than a small co-op housing association.)

Should the organization, unless prohibited by law, proactively advise the individual concerned that personal information has been shared with law enforcement authorities? Or disclose only when an access request is received.

The recent case of R. v. Chehil sheds an interesting light on an internal law enforcement cooperation policy.

In Chehil, a drug enforcement team at the Halifax Airport was allowed by Westjet administrative personnel to view the electronic passenger list of an overnight flight from Vancouver. Drug couriers often travel alone on overnight flights, purchasing a last minute, walk-up ticket in cash and checking a single bag. The police look for these kinds of indicators and the appellant fit the profile. His baggage was dog-sniffed upon arrival. When Mr. Chehil collected the bag, he was arrested and the bag opened — three kilograms of cocaine were inside.

At trial, the court held that the police viewing of Westjet’s electronic records violated Mr. Chehil’s Charter right to be free from an unreasonable search and seizure and excluded the results of the search. On appeal, the court reversed that finding. It held that PIPEDA does not extend the Charter’s constitutional protection of privacy to the broader category of personal information covered by that personal information protection law.

At trial, the court held that the police viewing of Westjet’s electronic records violated Mr. Chehil’s Charter right to be free from an unreasonable search and seizure and excluded the results of the search. On appeal, the court reversed that finding. It held that PIPEDA does not extend the Charter’s constitutional protection of privacy to the broader category of personal information covered by that personal information protection law.

The court essentially said if Westjet violated PIPEDA Mr. Chehil had recourse to the federal Privacy Commissioner. Any PIPEDA issue that existed in Westjet providing police access to their electronic records was separate from the issue of whether Mr. Chehil’s Charter privacy rights were violated and, by the way, those rights were not violated. (Another case that suggests PIPEDA is a regulatory as opposed to a quasi-constitutional statute.)

What is of interest here is the decision by local Westjet personnel to allow the authorities to “look” at the passenger information. The court noted:

“There was evidence from Westjet’s head of corporate security that in doing so, the employees of Westjet did not act in accordance with the company’s internal release policy.”

Once again, not only should you have a policy but make sure your people understand and follow it.

At the end of the day, when law enforcement authorities ask for personal information without a warrant or order, it comes down to a corporate decision. Asking about “lawful authority” only get you so far and organizations need to know whether and how they will respond to such requests.

Nice article Michael. We’re seeing more and more of these type of issues in Europe too. Its always a tough decision for businesses sitting on lots of data and regrettably some arms of law enforcement are better than others at making their requests in the proper form and with appropriate safeguards for the innocent.

I find it appalling that a corporation would so easily betray the privacy of their customers. I understand if there’s a warrant that has been issued, but otherwise, it’s completely ridiculous!